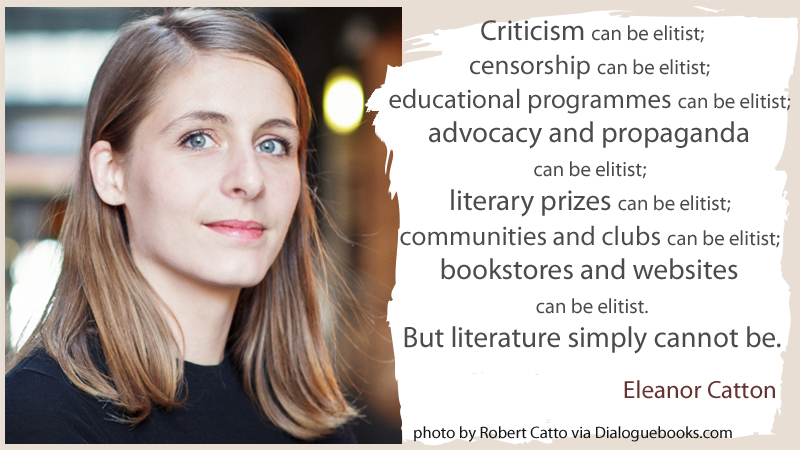

Is all literature for everybody? That is the question. Unlike Eleanor Catton, I believe that elitism of some sort cannot be avoided. What we call “literary fiction,” does not try to appeal to a certain type of reader, but still, nothing is for everyone, is it? I doubt that many authors will intentionally try to alienate any readers. It doesn’t make commercial sense. But, you will say, artists are not notorious for their commercial savviness. And you will be right. Some of them are, but many aren’t. What they may be known for is making art for art’s sake, which again is all about ignoring the reaction of the public. So if that author fancies herself or himself above everyone else in the room and wants everyone to see it, they will create elitist work. I don’t think elitism is beneath literature at all.

Is all literature for everybody? That is the question. Unlike Eleanor Catton, I believe that elitism of some sort cannot be avoided. What we call “literary fiction,” does not try to appeal to a certain type of reader, but still, nothing is for everyone, is it? I doubt that many authors will intentionally try to alienate any readers. It doesn’t make commercial sense. But, you will say, artists are not notorious for their commercial savviness. And you will be right. Some of them are, but many aren’t. What they may be known for is making art for art’s sake, which again is all about ignoring the reaction of the public. So if that author fancies herself or himself above everyone else in the room and wants everyone to see it, they will create elitist work. I don’t think elitism is beneath literature at all.

My thoughts about this have been prompted by a recent discussion (here and here) about elitism in the literary world, which was fueled by the a Twitter comment that the use of the word “crepuscular” in a piece published by “The Paris Review” was proof of elitism.

We often have this debate at my house: is a book better for using unusual words, or should writers strive to communicate their message in the simplest and most accessible way possible? Clearly, only fancy words do not make a book. But a simplistic vocabulary doesn’t either. A book is much more than the sum of its words, isn’t it? Word choice is not as simple as a choice between common and sophisticated words. Of course, the debate is wide ranging, but it all comes down to the intention of the writer, in my opinion. If “big” words are used just for the sake of their grandness, the text is elitist, but if they are used because no other word would do in that place at that time, then it’s just a good piece of literary work.

William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway had a famous vitriolic exchange regarding exactly this debate.

He has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary,

said William Faulkner about Hemingway

Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use,

Ernest Hemingway retorted.

To me Faulkner does sound elitist here and Hemingway sounds right. Writing should not be about sending the reader to the dictionary but about finding the best words. That being said, let’s not forget that words are immensely fascinating to people who write and you can’t blame us if sometimes we fall prey to the charms of one word or another and use it more liberally. There is not much fun we have in our lives.

PS. In researching this post I found an article in the Examiner.com titled “The 50 best author vs. author put-downs of all time,” about writers being mean to each other. It’s a fun read. They could be as elegant as Henry James disparaging Edgar Allan Poe,

An enthusiasm for Poe is the mark of a decidedly primitive stage of reflection.

As childish as Nathanier Hawthorne belittling Edward Bulwer-Lytton,

Bulwer nauseates me; he is the very pimple of the age’s humbug.

Or rather morbid and scary, though very creative, like Mark Twain’s dismissing Jane Austen’s work:

Every time I read “Pride and Prejudice,” I want to dig her up and hit her over the skull with her own shin-bone.

I know! Writers can be such meanies. I’ll avoid them on the playground from now on.

I take personal pride in being the “pimple of the age’s humbug”! So much to felx the thought muscles in this post, Lori – much enjoyed it!

Yes, you would!

Glad you enjoyed it, Rachel!

I take personal pride in being the “pimple of the age’s humbug”! So much to felx the thought muscles in this post, Lori – much enjoyed it!

Yes, you would!

Glad you enjoyed it, Rachel!