Beautiful Necessity, The Art and Meaning of Women’s Altars – the title of this book sounds very intriguing, right? I had to read it. And it started good. It seemed very interesting with a few initial references to altars in Romania. But something happened. Maybe it just wasn’t a good point in my life. Maybe this book sounds too much like a thesis for some professorate degree. I cannot put my finger on it. The magic was killed after a few initial pages.

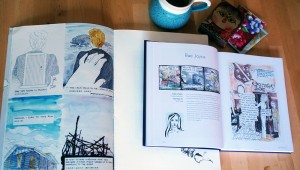

It really is what it says it is – a book defining, setting a place for women’s altars in history. I believe it to be an important book, an essential gathering of data to support the idea that all throughout time and place women have made home altars for their personal relationship with God, with the spirituality, away from the places dominated by men, like churches. The author is not making any effort to integrate the text too much, except for gathering the bits and pieces of her research under eight different chapters, all sprinkled from start to finish with more or less inspired photographs of personal altars, most of them coming from the south-american catholic tradition, but also hindu, african, christian orthodox, pagan, gay, artistic.

But still, the importance of this book cannot be denied, I believe. It brings forward the idea of a different spirituality of women, proven and documented. And I am not one to look at that lightly. The author talks about a duality of women as participants in the general culture and members of a women’s culture. She even shows that it is thought originally the iconic images to have been made for home use. For women. The ones generally excluded from the public religious scene. In the Christian church there is a big conflict surrounding the images of God. In my orthodox religion it is forbidden today to idolize gods in statue form. Catholics allow it. Painted icons are accepted though in orthodoxy too. But there was an initial current in the church to forbid all cult images. It was called the “iconoclast controversy” and its end was brought upon by a woman, according to Kay Turner. To consolidate their power, the clergy decided that no icon is proper unless it is blessed in the church, by the church. Worship of images was restricted and persecuted. But it was a woman who became regent of the Byzantine Empire in the year 780, Irene, who reinstated the cult of images.

So I would recommend this book to those scholarly inclined to research this area of women’s altars. It is an excellent resource and I am glad this book was written. I might even consider buying it for future reference.